Kevin Shoom on BEPS

This is an edited transcript of a presentation given on May 26, 2016 at the 2016 IFA (Canadian Chapter) Conference in Montreal by Kevin Shoom. He served as Senior Chief, International Taxation and Special Projects at the Department of Finance Canada, and at the time of presentation was working at the OECD's Centre for Tax Policy and Administration.

His slides are interspersed with the transcript, so that generally the slide(s) to which his comments were addressed appear immediately above those comments. He did not get to his final slides and skipped over a few of the earlier ones (all of which nonetheless are shown below).

Introduction

Thank you for giving me the opportunity to be with you here today. It is good to be back in Canada. I have a very large number of slides, probably too many to get through in the available time, so that I will probably be skipping through some of the material in order to try to keep the presentation to a reasonable length.

Principal topics

To outline what I am planning on talking about, I will have some comments on the BEPS project, and talk about some of the specific outputs, in particular: country-by-country (CbC) reporting; the work on intellectual property regimes which hopefully, in addition to some of the discussions we have already had today, will help set the stage for tomorrow’s discussion on IP issues; the transparency framework for rulings; and the inclusive framework about expanding the participation in the BEPS project to countries outside the OECD and the G20. I will also take advantage of the opportunity to comment at various points during my presentation, where relevant, on some of the questions and discussions that came up earlier in the day about some of these BEPS elements.

BEPS project: general comments

The BEPS project was launched in 2013, and last October the final package of reports was delivered to the G20. Now we are into the next phase, which involves a lot of work on implementation, and some final work on standard setting.

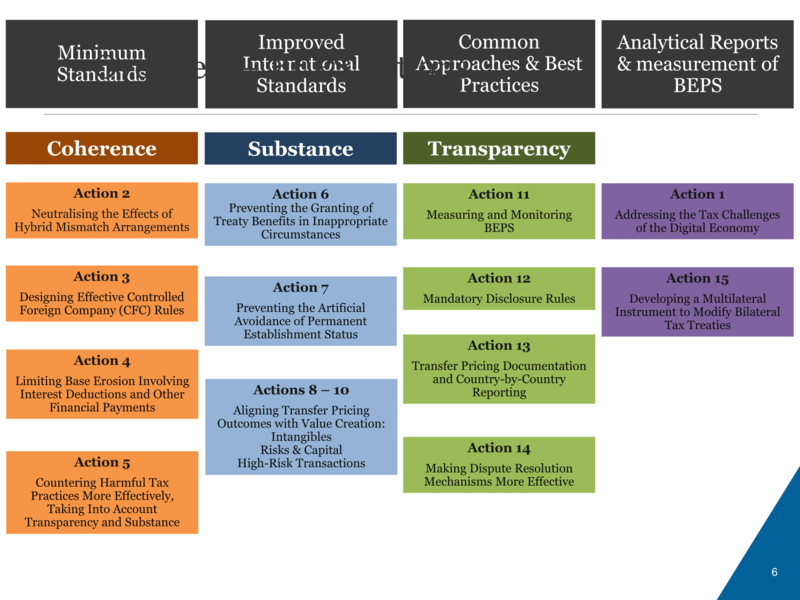

The slide shows the 15 actions including the three pillars of the BEPS project—coherence, substance, and transparency. Since BEPS has already been discussed earlier in the day, I will move on to see how those 15 actions line up as to the expectations for the countries to implement the outputs.

The work that I will be talking about in more detail - on CbC reporting and on Action 5 - fall under the Minimum Standards headings, which are of course the outputs where there is a clear expectation that all participants in the BEPS project will implement those outputs.

Double non-tax declaration

Before we go on, I did want to comment on the Action 6 standard. You will recall that there was a discussion this morning about whether the component of that report as to including a lengthy statement in tax treaties on the common intention to eliminate double taxation without creating opportunities for double non-taxation, was part of the minimum standards. I am not the expert on this Action, but I did check with my colleagues back in Paris and they confirmed that it is part of the minimum standards.

Country-by-Country Reporting

Monitoring of minimum standard

One of the aspects of the minimum standards is that the OECD is developing monitoring processes, which are in the process of being implemented in order to make sure that all members of the BEPS project will comply with the standards so as to help ensure a level playing field.

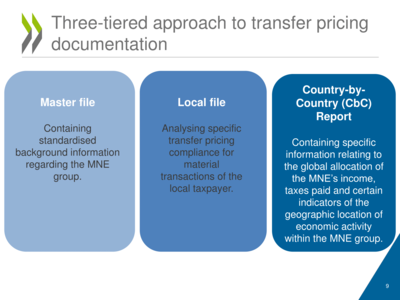

Three-tiered approach

Country-by-country reporting is, as you know, a part of Action 13, which proposed a three-tiered approach to transfer pricing documentation. What does it actually looks like?

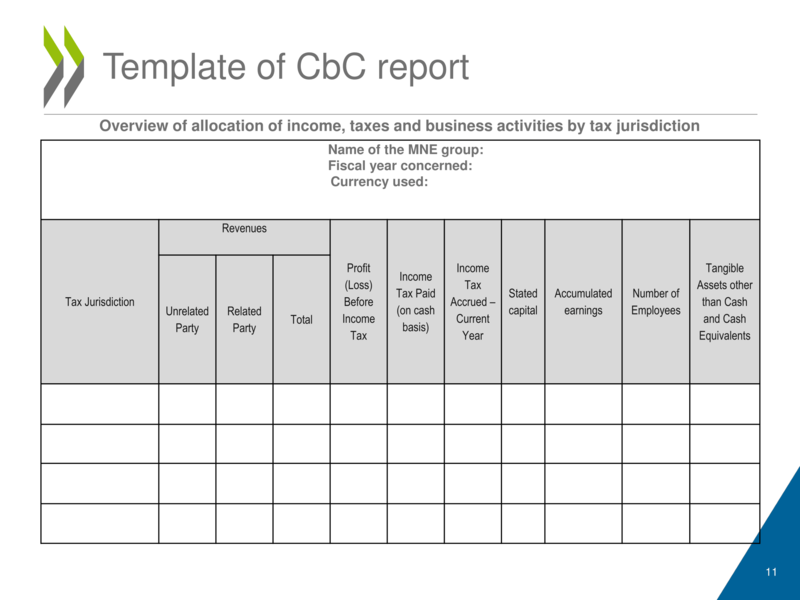

This is Table 1 of the report showing that there is a line (a row) for each jurisdiction in which the multinational operates. Not a line for each individual entity, but one for each jurisdiction. And there is also an opportunity for me to clarify another aspect of the discussions this morning, respecting the determination of the information to go into a particular line, and the need to work from individual entity accounts.

This was extensively discussed in the development of the Action 13 report: whether to take the so-called bottom-up approach of working from individual company accounts to create the line for the full country; or to work with a top-down approach in taking the group’s consolidated accounts and then breaking them down for individual countries. We consulted with stakeholders. Some said it was easier to go with the bottom-up approach, some said they preferred going with the top-down approach, and in the end the OECD decided to not take a position and so taxpayers actually under the Action 13 report have the option of which way to go. Having said that, of course an individual country’s implementation might differ.

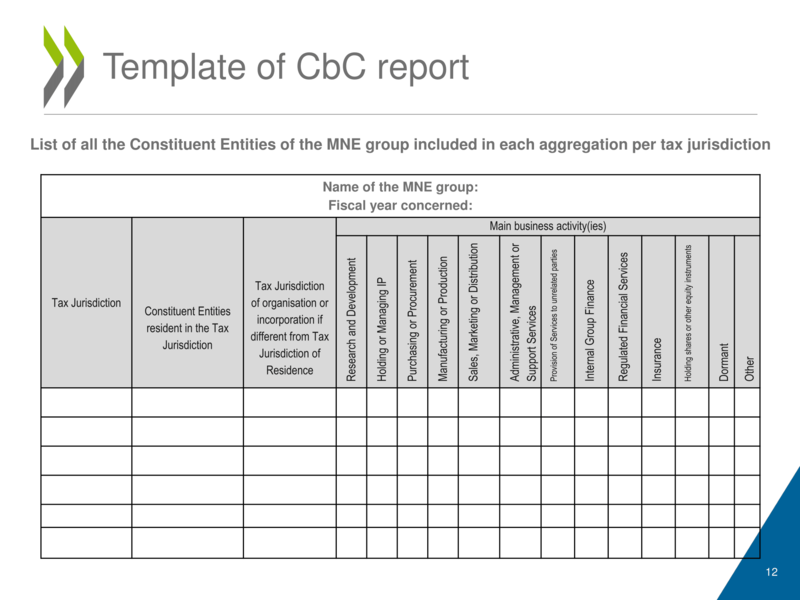

This is Table 2 of the report, and it does require a listing of each individual constituent entity of the multinational group. The only information which needs to be provided for each of these entities is where they are resident and their main business activities.

There is also Table 3. I do not have a slide on that, but I wanted to talk about how important and useful it is. However, an earlier session this afternoon, covered most of what I wanted to say about that. The only other thing that I will add is that the OECD is encouraging taxpayers to make use of Table 3, in the way that was described, in order to make sure that tax administrations have as much information as possible to help with interpreting the CbC report.

Implementing reporting

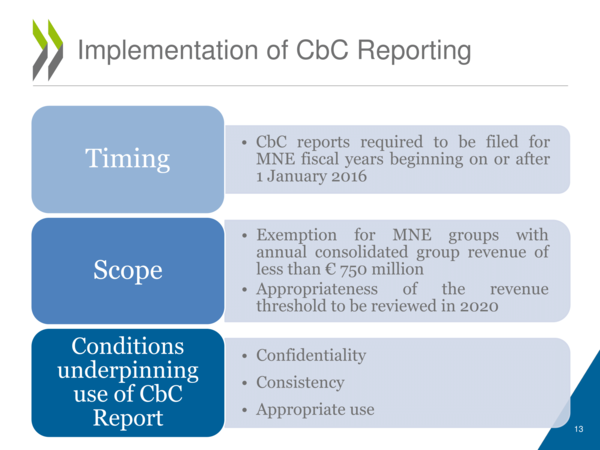

Thus, implementing the reporting involves considerations of the timing, the scope and the conditions for use. I will talk more about timing and conditions later. Respecting the scope, there are no exceptions for multinational enterprises (MNEs) in terms of business sector, or lines of business, but there is an exemption for groups with consolidated revenue of less than €750 million, and that should help to focus the reporting on the largest MNEs.

Filing mechanisms

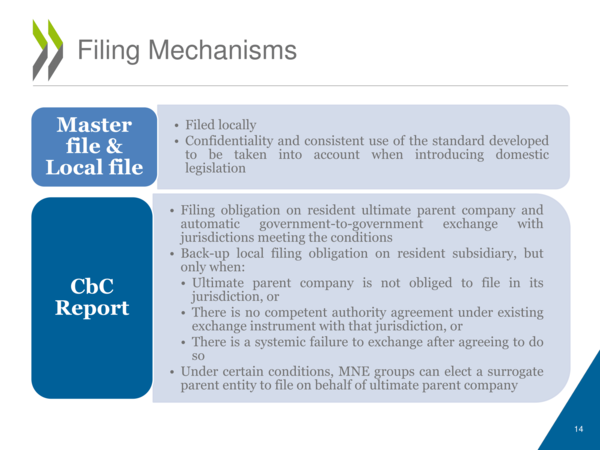

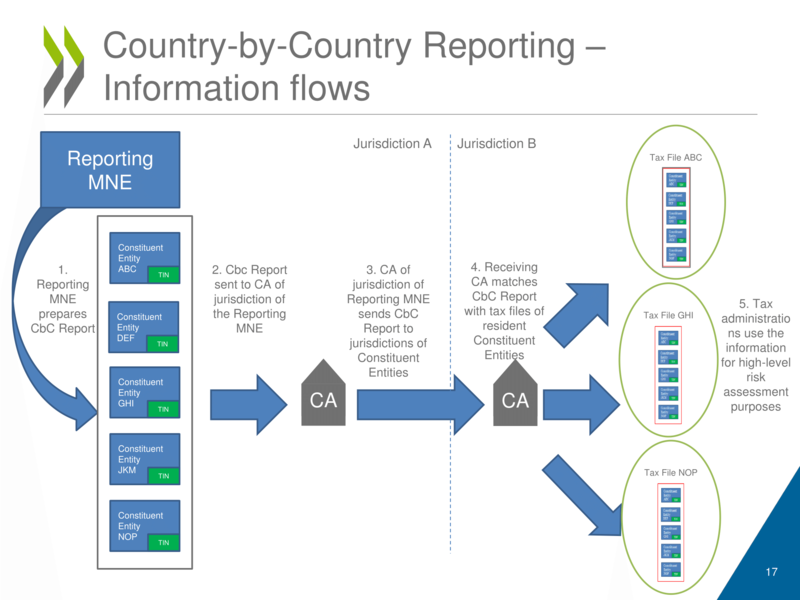

In terms of filing mechanisms, how will tax administrations obtain these reports from multinational groups? For the CbC report, the idea is, as most of you are aware, that the parent files the report in the jurisdiction in which it is resident, and then that jurisdiction’s tax administration exchanges the report using the exchange of information instruments with the other tax administrations in the other countries where the group operates. There is always the possibility that the group will be headquartered in a jurisdiction which has not implemented CbC reporting. The Action 13 report includes the possibility of what is called a back-up local filing option under which, if the parent is not filing a report, a country can impose the obligation to file the CbC report on its local entity. This could of course be onerous for some multinationals, so that the report also provides the so-called surrogate-parent option, which allows the multinational group to designate a member of the group to act as a surrogate for filing the report. It can then file the report in the jurisdiction where it operates, and that report can be exchanged the same way that would happen if the parent jurisdiction required exchanges - and that would turn off the back-up local filing obligation.

CbC reporting implementation

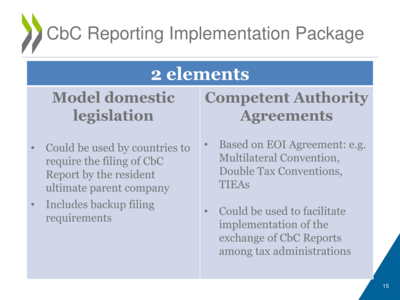

So the implementation package includes a model of domestic legislation to provide consistent implementation across countries and to speed up the implementation process, and it also includes a model competent authority agreements that would sit on top of instruments like bilateral tax treaties or the multilateral convention on mutual administrative assistance.

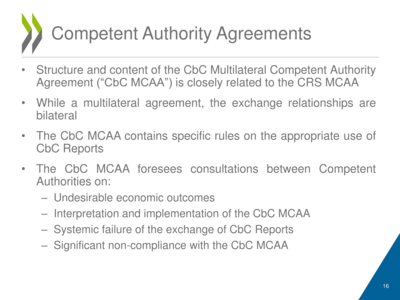

Competent authority agreement

The competent authority agreements include specific rules on the appropriate use of the CbC reports, and procedures that countries should follow if they consider that an exchange of information partner has not respected those restrictions. That is intended to help respond to concerns about individual countries possibly not respecting the restrictions on appropriate use. This slide talks about the multilateral competent authority agreement, which would sit on top of the multilateral convention and allow a large number of countries to agree to identical terms for the exchange of CbC reports in a streamlined manner.

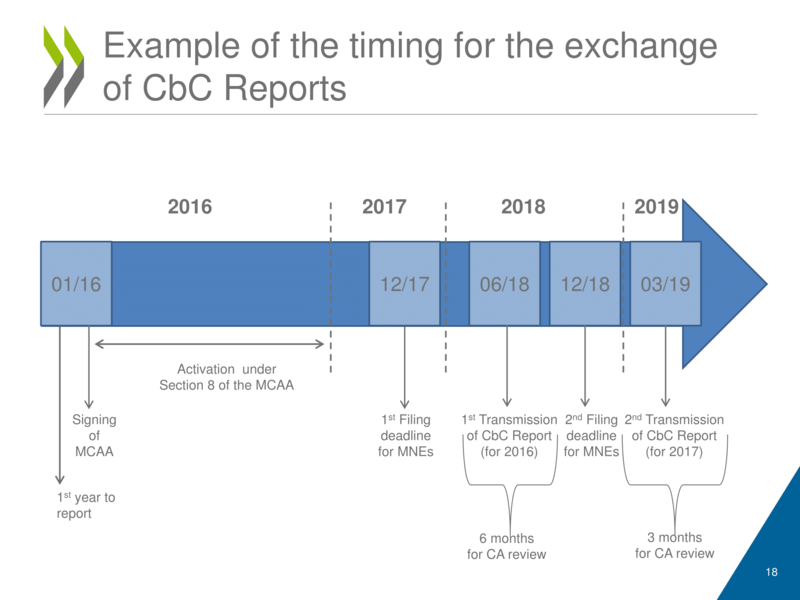

Timing for report exchanges

I now move on to timing. The first reports due are for tax years of multinational groups starting at the commencement of 2016. They are expected to file their reports within a year of their year-end, which generally means by the end of 2017. Tax administrations would then have up to six months to exchange the reports. This process then will be repeated in future years, except that the time allotted to the tax administrations to exchange, following that first year of exchange, would decrease to three months.

Technical implementation issues

A lot of technical work is going on at the OECD as well. We have developed an XML schema and user guide, which was released publicly in March of this year, providing a common exchange format which will help to increase the efficiency and reduce the chances of error in electronic exchanges of CbC reports. Furthermore, the forum on tax administration (FTA), which is a grouping of tax commissioners including a commissioner choice from the CRA, is collaborating on technical implementation issues associated with CbC reporting. I would emphasize that this particular work is actually being lead under the ITA by the CRA and they have been doing a very good job of it - so thanks to the CRA for that.

Domestic law changes

Progress is proceeding quite well - we are quite pleased to see a large number of countries that have implemented, or are in the process of implementing, their domestic law changes including Canada which addressed its intentions in the 2016 budget. 39 countries have signed the multilateral competent authority agreement so far, and we expect everyone to do so.

Conditions underpinning CbC

Now, for the condition underpinning the obtaining and using of your CbC report. The first one, is confidentiality. The countries agree that they will protect confidentiality to the same extent as under exchange of information standards. This is an opportunity for me to refer back to some of the morning’s discussions on the EU framework respecting expressions of concern by EU members about public disclosures in CbC reports.

Just in case it was not fully clear, there are actually two processes going on under the EU currently for CbC reporting. The first process is parallel to the process through the OECD and G20. The template would be the same and there would be confidentiality in the exchanges between tax administrations. That first initiative does not involve any public disclosure. That initiative, I believe, received approval from Eco-Fin yesterday.

The second initiative is the public disclosure of CbC reports. That would actually be a different CbC report than what we have been talking about so far. It would have less information in it (some of the columns that you saw earlier in Table 1 would not be there) and, as was talked about earlier, there would not be disclosure of every single country outside of the EU, only of certain countries which are identified as tax havens. That initiative is still at the proposal stage. The EU has not yet come to a final decision on it.

With respect to consistency, there is an agreement amongst the participants in the BEPS project that the CbC reports should contain the information that is in the template of the Action 13 report. Exactly that information: nothing more, and nothing less. I think that will be helpful in helping you address some of the concerns about the administrative burden on multinational groups that would have to comply. I think that is something Brian will be talking about more in a few minutes.

With respect to the appropriate use of CbC reports, there are, of course, restrictions in the exchange of information mechanisms about what countries can do with the reports they receive under those instrument. The Action 13 report contains additional restrictions on their appropriate use, essentially limiting the use of CbC reports to assessing high-level transfer pricing risks and other BEPS related risks, and stating that the reports cannot be used, for example, as the sole basis for a reassessment. There was some discussion earlier this morning about how those restrictions on use are going to be respected. In addition to the restrictions being in the report, they are also in the competent authority agreements, so that that is an additional mechanism for ensuring some discipline. Furthermore, the OECD will be developing a peer-review mechanism for CbC reporting to ensure that the various requirements are being met by the countries that are implementing CbC reporting, including that the appropriate use restrictions are respected.

Harmful Tax Practices

Moving onto the work at the OECD on harmful tax practices, designing tax policy is of course a sovereign right. However, the OECD members have recognized the interaction that individual country tax policies can have on each other and have thus agreed on a set of criteria to identify tax regimes that are considered to be harmful. These criteria were developed in 1998. The review of country regimes in determining whether the criteria apply happens through the Forum on Harmful Tax Practices (FHTP) body organized at the OECD.

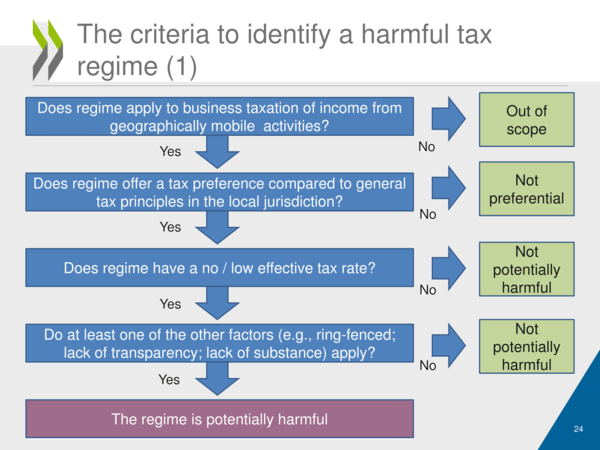

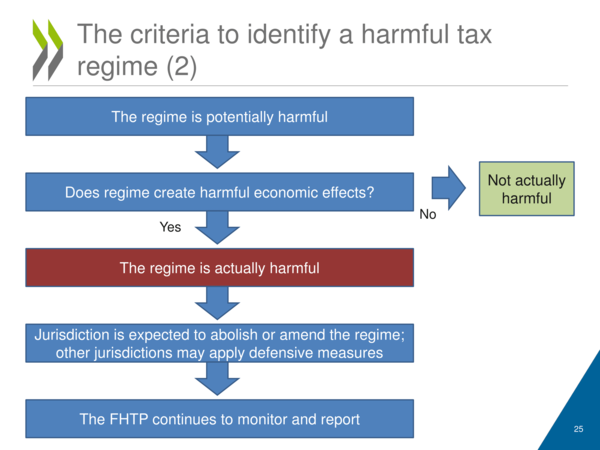

Criteria for harmful tax practice

FHTP criteria are set out in this slide and the next. I will not walk through these in detail, other than just to note that there are a variety of factors that need to be assessed (a variety of decision points that need to be gone through) before determining whether a regime is actually potentially harmful. Once we reach that point, there is an evaluation of whether the regime is harmful in practice based on whether the regime has harmful economic effects. If a regime is determined to be actually harmful, there is an expectation that the jurisdiction will abolish or amend the regime. It also gives scope for other countries to apply defensive measures against that regime.

IP regimes

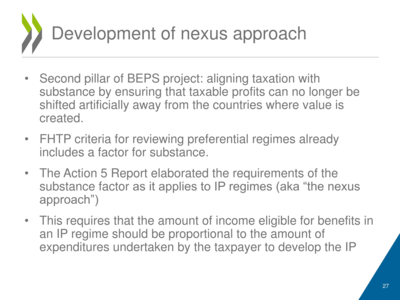

Within the context of work on harmful tax practices, and under Action 5 of the BEPS project, one of the main outputs relates to intellectual property regimes. This ties into the second pillar of the BEPS project, about aligning taxation with substance. The FHTP's criteria have already included a factor related to substance: a substantial economic activity is required to benefit from the preferential tax regime.

The Action 5 report elaborated requirements of the substance factor as it applies to IP regimes, and this is known as the Nexus Approach. In essence, the Nexus Approach requires the amount of income eligible for benefits in an IP regime to be proportional to the amount of expenditures undertaken by the taxpayer to develop the IP.

I just want to pause here to note that there was a question raised this morning about whether the Nexus Approach, when implemented within the EU, will it be consistent with EU law. I am with the OECD Secretariat. I am not with the European Commission, so I cannot speak with any authority on EU-law issues, but I will note that the requirement here is about the expenditures needing to be undertaken by the taxpayer. It does not specify that they need to be undertaken by the taxpayer within the jurisdiction offering the regime - so they could, in theory, be undertaken by a PE of the taxpayer in another jurisdiction. In this respect, I have a general comment that the OECD does include a lot of members of the EU and it is often the case that, in discussions at the OECD about where to go on a particular issue, that the EU members around the table will bring up questions of EU law and the necessity of trying to design rules and guidance that also work within the EU law framework.

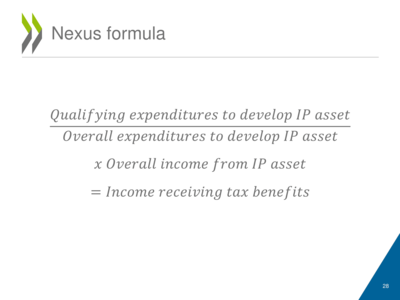

Nexus formula

The Nexus Approach has been implemented with the so-called nexus formula. The first part of the formula is the so-called nexus ratio, at the top of the screen, involving the ratio of: qualifying expenditures to develop the IP asset; over overall expenditures. The main difference between qualifying expenditures and overall expenditures would be things like acquisitions of IP or outsourcing to related parties. For example, if a taxpayer conducts all the work to develop the IP asset (e.g., R & D) in-house, then this nexus ratio would be equal to one. That ratio is then applied to the overall income from the IP asset, to determine the amount of income which is eligible to receive benefits under a preferential regime.

Nexus implementation

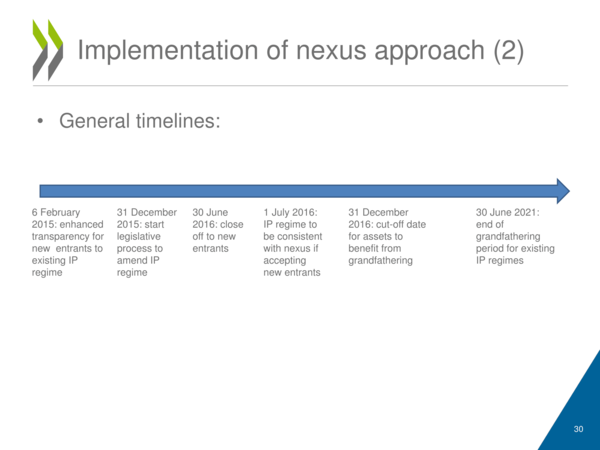

In the process of developing the Nexus Approach, 16 IP regimes were identified in OECD and G20 countries. They were all found to be, in whole or in part, inconsistent with the Nexus Approach. Therefore, there is an expectation that the countries will consider the amendments necessary to bring them into conformity with the Nexus Approach. Several countries already have work on this underway, and this is something that the FHTP is going to be monitoring and reviewing. We are doing a lot of work right now to develop our process for doing that.

In terms of the timelines for implementing the Nexus Approach, the key date to mention here is the 30th of June, 2016, which is the last day on which those regimes which are not fully compliant with the Nexus Approach can accept new entrants. As of July 1st, those non-conforming regimes are expected to be closed off to new entrants. IP assets that were already in existing regimes do have the potential to benefit from that grandfathering for up to five years.

Rulings Disclosure

Transparency framework

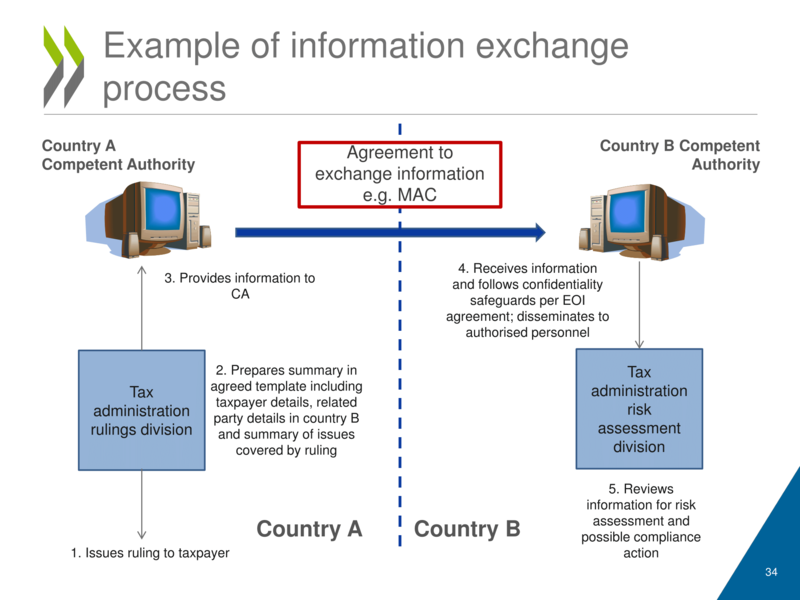

Moving onto the other part of the output under Action 5, the transparency framework for rulings, this ties into the third pillar of the BEPS project - on transparency. The FHTPs criteria had already included a factor for transparency, and other expectations related to spontaneous exchanges respecting rulings. The Action 5 report provides a detailed framework requiring spontaneous exchange of information on taxpayer rulings. In this respect, I will note that this report does not seem to directly involve taxpayers: it is really just about the exchange of information between tax administrations on rulings - but taxpayers should be aware of the information that will now be made available automatically to other tax administrations on this spontaneous basis.

The CRA issued an Information Circular on April 22nd (thanks to Mr Bowman for bringing this to my attention), which sets out the CRA’s position with respect to approaching this requirement for the spontaneous exchange of rulings.

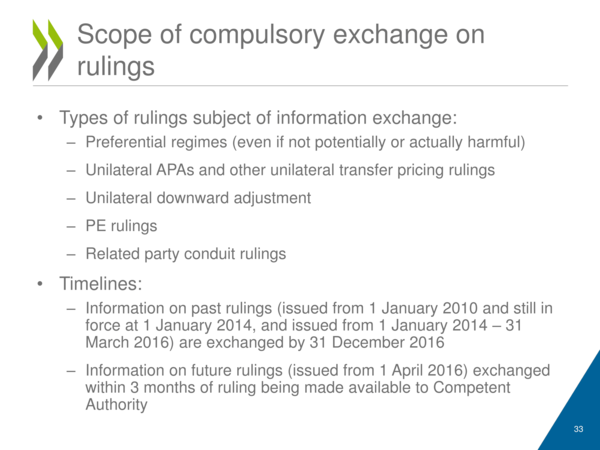

Scope of compulsory exchange

As to the scope of the exchanges on rulings, first the changes will not be of the full rulings, they will be of summaries of the rulings. Second, the types of rulings that are subject to information exchange are: any rulings related to preferential regimes; rulings related to unilateral APAs; unilateral transfer pricing rulings; and what we term unilateral downward adjustments (which would include the types of regimes in Belgium and the Netherlands which were discussed this morning [excluding excess profits from income]. In terms of that, there was some interest this morning of the panelists about how the EU is approaching the regimes in Belgium and the Netherlands for excess profits etc. The way the OECD is approaching these, for the time being, is not considering whether they constitute harmful tax practices - but instead relying on transparency, so that tax administrations that provide these regimes are expected to engage in automatic spontaneous exchanges of information on the granting of these benefits under these regimes.

Furthermore, this morning the question was raised about the distinction between regimes which are based on rulings and those that are based solely on law. That distinction does not make a difference under the OECD’s approach. Whether it requires a ruling, or whether taxpayers can simply claim benefits under their domestic law, there is still a requirement for countries to exchange information on those adjustments.

There are also the requirements to exchange respecting PE rulings and related party conduit rulings. The timelines for implementing this part of the minimum standard: for rulings which were issued up until the end of March of this year, the information is required to be exchanged by the end of this year; and for rulings issued starting April 1st of this year, they are to be exchanged within 3 months.

Other

FHTP work on 2016 onwards

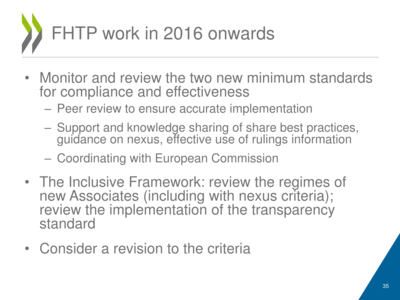

Moving on to the FHTP’s work generally, a big part of our work, as I said, will be monitoring or reviewing these minimum standards in order to ensure compliance and effectiveness. This includes the peer review process to ensure accurate implementation by members of the FHTP.

I will clarify here one of the points raised this morning about the information related to IP regimes. The Action 5 report requires that countries that provide IP benefits are required to report certain information on those regimes to the OECD. They are also required to engage in certain exchanges under the transparency framework related to those regimes, and those requirements do form part of the minimum standard and will be monitored as part of this peer-review process. We are also working on providing support to member countries, we acknowledge sharing best practices etc. to help with the implementation, and we are coordinating with the European Commission given that the EU does have a parallel framework for rulings transparency. It also has decided to implement the Nexus Approach as a way of evaluating IP regimes under its Code of Conduct group. So we are working with the Commission in order to make sure that their implementation and our implementation work together as harmoniously as possible.

We are also looking forward, with the expansion of the OECD’s tax work under the inclusive framework that will bring in a lot of new members. That also means potentially lots more preferential regimes which we will need to be reviewed under the criteria which I talked about earlier. Again, a bit of clarification on the discussion this morning about reviewing what we call special development zones. The Action 5 report does have a discussion about what we call regimes relating to disadvantaged areas which could include these zones. It contains rules as to what these areas can look like and reporting requirements associated with them - and so, just to confirm, these also form part of the minimum standard.

Inclusive Framework

The final part of my presentation, is on the inclusive framework. [This was not presented due to insufficiency of time, although the following comment was made:]

I will just make the one final comment on the inclusive framework, which is to note that this is really a sea change for the tax work at the OECD. With so many countries that will be coming into this, the existing membership of the OECD (perhaps augmented by the G20 members) are going to be in the minority around the table. Most of the countries around the table will be non-OECD, non-G20 economies. They will be participating on an equal footing, they will be committed to the same outputs the way OECD members are, and we are really looking forward to the new dynamic this will bring to the tax discussions.