27 October 2020 CTF Roundtable - Official Response

Presented by:

Yves Moreno, A/Director, International Division, Income Tax Rulings Directorate, CRA; and

Stéphane Prud'Homme, Director, Reorganizations Division, Income Tax Rulings Directorate, CRA

Unless otherwise stated, all statutory references in this document are to the Income Tax Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. 1 (5th Suppl.) (the “Act”), as amended to the date hereof.

Question 1: ACB increase in a reorganization caused by a misalignment of outside and inside ACB

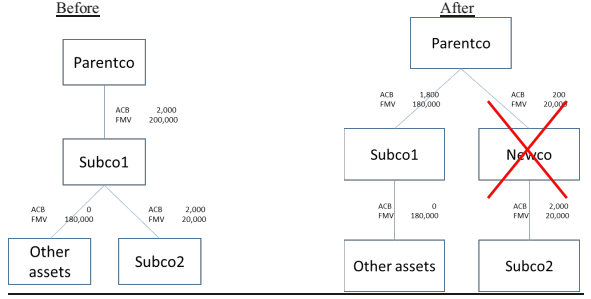

Consider the following situation:

- Parentco originally incorporated Subco1 and subscribed for shares of Subco1 with an ACB of $2,000 on incorporation.

- Subco1 incorporated Subco2 and subscribed for shares of Subco2 with an ACB of $2,000 on incorporation.

- Subco2’s value increased to $20,000. Subco2 did not realize any safe income.

- The value of other assets in Subco1, which was nil on incorporation of Subco1, increased to $180,000. Subco1 did not realize any safe income.

- Parentco, Subco1 and Subco2 are Canadian-controlled private corporations.

- It is proposed that Subco1 transfers Subco2 to Newco, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Parentco, in a reorganization that qualifies under either paragraph 55(3)(a) or 55(3)(b) of the Act. The steps of the reorganization would be as follows:

- Parentco transfers shares of Subco1 having an ACB of $200 ($2,000 x $20,000/$200,000) and a FMV of $20,000 to Newco on a rollover basis in consideration for shares of Newco.

- Subco1 transfers shares of Subco2 to Newco on a rollover basis in consideration for shares of Newco.

- The shares held between Subco1 and Newco are cross-redeemed.

- Newco is subsequently wound-up into Parentco. Subsection 88(1) applies to the wind-up.

Before the reorganization, Parentco owned shares of Subco1 with an ACB of $2,000 and a FMV of $200,000. Subco1 owned assets with an aggregate ACB of $2,000 and an aggregate FMV of $200,000.

After the reorganization and the wind-up of Newco, Parentco will own shares of Subco1 with an ACB of $1,800 and a FMV of $180,000 and shares of Subco2 with an ACB of $2,000 and a FMV of $20,000. In aggregate, the assets owned by Parentco after the reorganization and wind-up of Newco will have an ACB of $3,800 and a FMV of $200,000. Subco1 will own assets having no ACB and a FMV of $180,000. Does the CRA have any concern with this situation?

CRA Response

We recently received a ruling request with respect to a similar reorganization and we were unable to issue a favourable ruling in that regard based on the following considerations:

- Let’s consider the following distinct possibilities if there was no reorganization:

- If Subco1 sold all of its assets at FMV, a total capital gain of $198,000 would be realized by Subco1. Subco1 could then distribute the after-tax money to Parentco. Suppose the net tax to be paid by Subco1 (ignoring the RDTOH refund and Part IV tax mechanism) is $39,600, based on a hypothetical tax rate of 40%, Parentco would be entitled to receive $160,400 from Subco1 on a tax-free basis, i.e., as a return of capital of $2,000, a CDA dividend of $99,000 and a safe income dividend of $59,400.

- If Parentco sold Subco1 at FMV, a capital gain of $198,000 would be realized by Parentco. On an after-tax basis, it’s the same as if Subco1 sold the assets and distributed the after-tax money to Parentco, i.e., Parentco would retain $160,400 after tax.

- The results discussed in a. and b. above are due to the integration mechanism in the corporate tax system.

- If Subco1 only sold Subco2 and distributed the after-tax money to Parentco, it would realize a capital gain of $18,000. Assuming the same tax rate as above of 40% and ignoring the RDTOH and Part IV tax mechanism, Subco1 would pay $3,600 of tax and would be able to distribute to Parentco $9,000 of CDA dividend and $5,400 of safe income dividend. Subco1 could also reduce PUC on the shares held by Parentco for $2,000 tax-free. However, any payment of a taxable dividend by Subco1 to Parentco in excess of $5,400 would attract the scrutiny of subsection 55(2) since the latent gain on the remaining assets of Subco1 has not been realized.

- Because Parentco has in fact exchanged shares of Subco1 having an ACB of $200 for shares of Subco2 having an ACB of $2,000 as part of the reorganization, Parentco has obtained an increase of $1,800 in ACB that is equivalent to a reduction of tax of $360. This result is a form of duplication of tax basis on assets held by Parentco. If Parentco were to sell Subco1 and Subco2 after the winding-up of Newco, it would realize a capital gain of $196,200 (instead of $198,000 as discussed above) and the applicable tax amount would be $39,240 (instead of $39,600 as discussed above).

- If Newco was not wound-up and it disposed of the shares of Subco2 and then made a distribution to Parentco, the results are the same as discussed in 1.d. above. Newco would have an after-tax cash of $16,400. It would be able to make a tax-free distribution to Parentco of only $14,600, i.e., $9,000 of CDA dividend, $5,400 of safe income dividend and $200 of PUC reduction. The excess of $1,800 would attract the scrutiny of subsection 55(2) if distributed as a taxable dividend. If shares of Newco were redeemed to inappropriately take advantage of the paragraph 55(3)(a) exemption, the CRA would consider the application of GAAR.

- Although the possible exchange of shares of Subco1 by Parentco prior to their transfer to Newco and the transfer itself may have complied with subsection 51(1), 86(1) or 85(1), a misalignment of outside ACB (i.e., ACB in the shares of Subco1 and Newco held by Parentco) and inside ACB (i.e., ACB in the assets held by Subco1 and Newco) on the reorganization followed by a winding-up of Newco provide an inappropriate result. In this type of situation, the CRA would not rule favourably and would consider the application of GAAR because there is an undue increase in ACB in the hands of Parentco that is against the scheme of the Act and particularly of subsection 55(2).

- This winding-up under subsection 88(1) has to be distinguished from a “normal” winding-up under subsection 88(1) where a parent would have inherited assets of a subsidiary that have an ACB higher than the ACB of the shares of the subsidiary held by the parent and where the difference between the outside ACB and the inside ACB is not due to a bargain purchase. In those “normal” winding-ups, the ACB of the assets of the subsidiary would normally be supported by after-tax money earned by the subsidiary, i.e., safe income. In the situation discussed above, the subsidiary, Newco, has acquired assets in a tax-free reorganization in which high ACB is pushed into the subsidiary while the outside ACB is low.

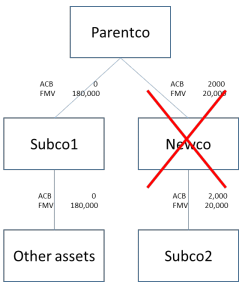

- A favourable ruling could be obtained in this situation if Parentco transferred enough ACB in the shares of Subco1 to Newco to cover the ACB (and any safe income that can be crystallized into ACB) of the assets to be transferred to Newco. This would result in an alignment of inside and outside ACB. The picture prior to the winding-up of Newco would be as follows:

Question 2: Consolidation of safe income in a corporate group

Could the CRA reiterate its views on the consolidation of safe income in a corporate group?

CRA Response

Because of the wording “income earned or realized by any corporation,” it has been the CRA’s long-held view that a corporation can consolidate safe income of other corporations in which it has significant influence. The reason for the condition of “significant influence” was simple and practical: how could one expect to be able to access the financial and other information and to calculate safe income of corporations in which one does not have significant influence? In 1984, the CRA expanded its position as follows:

In 1981, Revenue Canada (subsequently referred to as “the Department“) indicated that the word “any” in the phrase “income earned or realized by any corporation” permits the consolidation of safe income within a corporate group. In cases where a corporation does not exercise significant influence over another corporation in which it owns fully participating shares, the safe income of the corporation should include only dividends received from the other corporation to the extent that they were paid out of safe income of the payer corporation. After facing this issue in many factual situations, the Department is prepared to make an exception in cases where a corporation does not exercise significant influence, if it can be clearly demonstrated that the income of the other corporation contributed to the unrealized gain on the shares. [emphasis added]. [2]

The position adopted in 1984 is still valid and very relevant today. One can consolidate safe income of a corporation over which there is no significant influence if it can be clearly demonstrated that the safe income of such corporation contributes to the gain on the shares, bearing in mind that, in the case of portfolio investments in public corporations, what would be considered to contribute to the value of the shares held by the shareholder is not the income of the public corporations but rather the trading value of its shares on the stock exchange.

The above discussion would also apply to consolidation of income from foreign corporations that are not foreign affiliates of the shareholder, as confirmed in Lamont. [3]

With respect to negative safe income, the CRA is of the view that the negative safe income of corporations would reduce the safe income of a holding corporation only to the extent that it can be considered to result in a reduction of the value of the shares of the holding corporation, for example, either because of a guarantee made by the holding corporation, or because of an actual payment for the losses by the holding corporation. This position is in line with Brelco. [4]

Question 3: Safe Income on Reorganization

What guidance can the CRA provide regarding the impact of reorganizations on safe income?

CRA Response

This is a very complex issue that has not been addressed before. Since the legislation on safe income is relatively minimal, the CRA recognizes its stewardship role in this area, as it is essential to provide taxpayers and their advisors with guidance and tools to better fulfill their tax obligations.

The entitlement to safe income hinges on whether the income earned or realized could “reasonably” be considered to contribute to the accrued gain on the shares,[5] the theory being that the income earned or realized by the corporation could somehow contribute to the increase in the value of the shares and, since such income earned or realized has already been subject to tax, a dividend paid by the corporation that reduces the portion of a capital gain on a share that represents such increase should not be subject to additional tax.

The concept of safe income is paramount because the safe income allows for tax-free distributions between corporations since income already subject to tax inside a corporation should not again be subject to tax upon distribution. Furthermore, corporations should not be allowed to make tax-free distributions that have a purpose of reducing value or increasing cost when the money used for such distribution or the money received on such distribution, has not been or will not be subject to tax anywhere. So, a proper calculation of safe income would help avoid double taxation as well as non-taxation. It is recognized by Kruco [6] that

[45] It is apparent from this brief analysis that Brown and McDonnell correctly identified the intent behind subsection 55(2) when they wrote the passage quoted by the Tax Court Judge at paragraph 82 of his reasons: The intent of subsection 55(2) is to permit a tax-free, inter-corporate dividend to be paid to reduce a potential capital gain to the extent that the gain is attributable to the retention of post-1971 income. Conversely, it is intended to block a dividend payment that goes beyond this amount to reduce capital gains attributable to anything other than retained post-1971 income.

To repeat, the main crux of the safe income determination is contained in two words of paragraph 55(2.1)(c): “reasonably” and “contribute.” A proper understanding of those two words, based on the respect of the scheme of subsection 55(2), is therefore crucial.

The CRA views on safe income follow the textual, contextual and purposive interpretation principles. They are not just a one-sided and self-serving interpretation of the rules. In the examples provided below, the CRA strives to be balanced and reasonable in its approach, in accordance with the corporate tax integration scheme, the concept of cost and the scheme of subsection 55(2) that prevents artificial creation or duplication of cost, and its willingness to consider solutions that avoid the loss of safe income to a taxpayer. The approach is based on the same principles that guided the response to Question 1 and the reasoning previously provided in documents 2016-0671501C6 and 2018-0780071C6.

As discussed in Question 2, the safe income can be consolidated. Safe income realized by a corporation will be referred to as “direct safe income” (“DSI”) while safe income consolidated from another corporation will be referred to as “indirect safe income” (“ISI”).

As a summary of the examples provided below, where an internal reorganization is effected on a pure rollover basis (i.e., all the properties are transferred at cost amount), the principles to be retained are the following:

- DSI of a transferor or a transferee is to be determined based on the proportion of cost amount of property retained by the transferor or transferred to the transferee and not based on the proportion of shares or accrued gain on the shares transferred.

- ISI of a transferor or a transferee is to be determined based on the proportion of ISI retained by the transferor or transferred to the transferee. The ISI retained or transferred is based on the subsidiaries that are retained or transferred.

- In certain circumstances as illustrated in Examples 3 and 4, it would be appropriate to stream the ACB of the shares held by a shareholder in a transferor corporation into shares that are to be transferred to a transferee corporation although, as a general rule, ACB should not be streamed prior to an internal reorganization since streaming could be abusive in certain circumstances and could be challenged by the CRA.

Where a transfer of shares is made at an elected amount higher than cost amount, the DSI and ISI that are to be transferred to the transferee corporation may be viewed as having been capitalized in the adjusted cost base of the shares transferred and would have to be reduced accordingly.

Example 1 [basic example that illustrates split of DSI]

In this situation, Opco was wholly-owned by Holdco.

Opco realized an after-tax income of $1,000. The income is reflected in the cost of Asset 2 owned by Opco (i.e., Opco purchased the Asset 2 with the income realized, after tax). Thus, the DSI of Opco to Holdco was $1,000. The DSI of Opco contributed to the gain on the shares of Opco. There was an accrued gain of $2,000 on the shares of Opco held by Holdco.

Opco proceeded to spin out Asset 2 to Newco, a corporation that is wholly-owned by Holdco, in a reorganization that qualified for the paragraph 55(3)(a) exemption. To effect the spin-off, Holdco transferred shares of Opco with an ACB of nil and a FMV of $1,000 to Newco in consideration for shares of Newco. Opco then transferred Asset 2 to Newco in consideration for shares of Newco. The shares held by Newco in Opco and by Opco in Newco are redeemed for a note and the notes are cross-cancelled.

After the spin-off, Holdco owned shares of Opco with an ACB of nil and a FMV of $1,000 and Opco owned Asset 1 with an ACB of nil and a FMV of $1,000. Holdco also owned shares of Newco with an ACB of nil and a FMV of $1,000 and Newco owned Asset 2 with an ACB of $1,000 and a FMV of $1,000.

How should the safe income of Opco be allocated after the reorganization?

In this scenario, the Asset 2 with the ACB of $1,000 was transferred to Newco. The DSI of Opco was used to acquire the ACB in Asset 2. It would not be appropriate that the DSI of $1,000 or a portion thereof remains with the shares of Opco held by Holdco.

In this scenario, although 50% of the shares of Opco are transferred to Newco to achieve the reorganization, all the DSI of Opco held by Holdco has been transferred over to Newco because it is reasonable to view that the DSI of $1,000 contributes to the gain on the shares of Newco held by Holdco after the reorg and that the DSI of $1,000 does not contribute to any gain on the shares of Opco retained by Holdco since the unrealized gain remains in the assets retained by Opco. Therefore, the DSI of Opco held by Holdco is not prorated based on the accrued gain on the shares of Opco and Newco after the reorganization.

The formula to do the allocation of DSI would be as follows:

DSI on the shares of Newco: DSI of Opco prior to reorg X cost amount of assets transferred to Newco / total cost amount of assets of Opco prior to reorg

DSI on the shares of Opco after reorg: DSI of Opco prior to reorg X cost amount of assets retained by Opco / total cost amount of assets of Opco prior to reorg

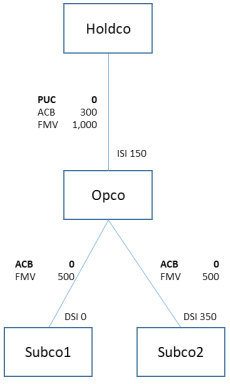

Example 2 [basic example that illustrates split of ISI]

In this situation, Opco did not realize any income. The income was realized in Subco2. Thus, the DSI of Subco2 held by Opco was $1,000 and Holdco had an ISI of $1,000 in Opco (due to the DSI of $1,000 in Subco2 held by Opco).

Opco transferred Subco2 to Newco in a reorganization that qualifies for an exemption under paragraph 55(3)(a). To effect the spin-off, Holdco transferred shares of Opco with an ACB of nil and a FMV of $1,000 to Newco in consideration for shares of Newco. Opco then transferred the shares of Subco2 with an ACB of nil and a FMV of $1,000 to Newco in consideration for shares of Newco. The shares held by Newco in Opco and by Opco in Newco are redeemed for a note and the notes are cross-cancelled.

In this scenario, Subco2 was transferred over to Newco with an ACB of nil.

Since the shares of Subco2 are transferred to Newco on a rollover basis, the DSI of $1,000 that Opco had in Subco2 is transferred over to Newco. Newco will have DSI of $1,000 on the shares of Subco2.

On a consolidated basis, the shares of Newco held by Holdco have an ISI of $1,000. Since the ISI of Holdco in Opco is now fully transferred over to Newco, Holdco should no longer have ISI in the remaining shares owned in Opco. The unrealized gain on the remaining Opco shares held by Holdco is supported by the unrealized value of the shares in Subco1, with no underlying safe income. In contrast, the unrealized gain on the Newco shares is fully supported by the DSI in the Subco2 shares. Note that we do not consider that the ISI of Holdco in Opco is prorated based on the accrued gain on the shares of Opco and Newco after the reorganization.

The formula for calculating ISI (below the Newco level) should be as follows:

ISI on the shares of Newco: ISI to Holdco on the shares of Opco (that excludes the DSI of Opco) prior to reorg X ISI to Holdco of entities held by Opco that are transferred over to Newco / total ISI to Holdco of all entities held by Opco prior to reorg

ISI on the shares of Opco after reorg: ISI to Holdco on the shares of Opco prior to reorg X ISI to Holdco of entities held by Opco that are retained by Opco / total ISI to Holdco of all entities held by Opco prior to reorg

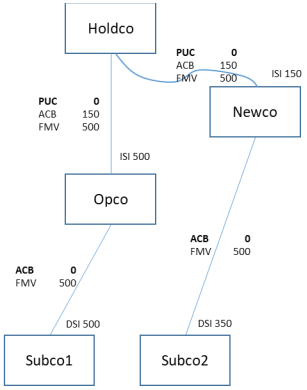

Example 3 [example that shows the interaction of outside ACB and inside ACB]

In this scenario, Holdco acquired Opco for $300 a few years ago. At that time, the DSI that Opco had was 0 and the DSI of Subco2 was $200 (Subco2 had a value of $300 and Subco1 had no value and no DSI at that time). Subco2 realized an additional DSI of $150 since the acquisition of Opco by Holdco and its value increased to $500. Subco1 realized no additional DSI after the acquisition of Opco by Holdco and its value increased to $500.

Therefore, even though the shares of Subco2 owned by Opco now have a DSI of $350, the ISI of Opco with respect to the shares of Subco2 is $150. The DSI of $200 of Subco2 pre-acquisition of control is reflected in the ACB of the Opco shares held by Holdco.

The shares of Opco held by Holdco have an ACB of $300 and a FMV of $1,000.

The shares of each of Subco1 and Subco2 held by Opco have an ACB of nil and a FMV of $500.

If safe income were to be capitalized before the reorganization, Subco2 would be able to pay a DSI of $350 to Opco and Opco would be able to pay an ISI of $150 to Holdco. Therefore, after capitalization of safe income, the situation would be as follows:

In this situation, Holdco has an ACB of $450 in the shares of Opco and, if Opco were to be wound-up, Holdco would directly own shares of Subco1 and Subco2 with an aggregate ACB of $350. Therefore, in this situation, the maximum ACB that Holdco could have in its subsidiaries does not exceed $450.

First reorganization possibility

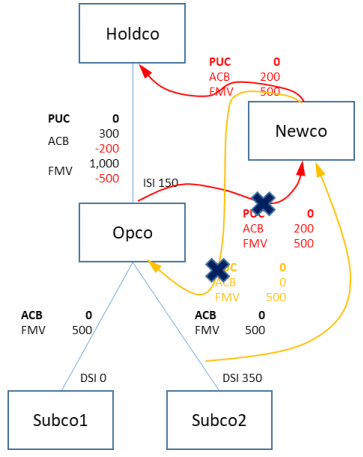

Without going through the capitalization of safe income, Opco transferred Subco2 to Newco in a reorganization that qualified for the exemption under paragraph 55(3)(a). To effect the spin-off, Holdco transferred shares of Opco having an ACB of $150 and a FMV of $500 to Newco in consideration for shares of Newco. Opco then transferred shares of Subco2 having an ACB of nil and a FMV of $500 to Newco in consideration for shares of Newco. The shares held by Newco in Opco and by Opco in Newco are redeemed for a note and the notes are crosscancelled.

Since the shares of Subco2 are transferred to Newco on a rollover basis, the DSI of $350 that Opco had in Subco2 is transferred over to Newco. Newco will have DSI of $350 on the shares of Subco2.

On a consolidated basis, the shares of Newco held by Holdco have an ISI of $150 since it represents the ISI of Opco that was transferred over to Newco.

Since ISI of Holdco in Opco is now fully transferred over to Newco, Holdco should no longer have ISI in the remaining shares owned in Opco. The unrealized gain on the remaining Opco shares held by Holdco is supported by the unrealized value of the shares in Subco1, with no underlying safe income.

However, the reorganization results in an inappropriate duplication of ACB because of the misalignment of outside and inside ACB as illustrated in Question1. If the ISI that Holdco has in the shares of Newco and the DSI that Newco had in the shares of Subco2 were to be capitalized after the reorganization, Holdco would have an ACB of $300 in the shares of Newco and Newco would have an ACB of $350 in the shares of Subco2. On a possible wind-up of Newco, Holdco would own shares of Subco2 with an ACB of $350. Holdco would have an aggregate ACB of $500 in the shares of Opco and Subco2 after the wind-up of Newco. This situation would not be acceptable.

Second reorganization possibility

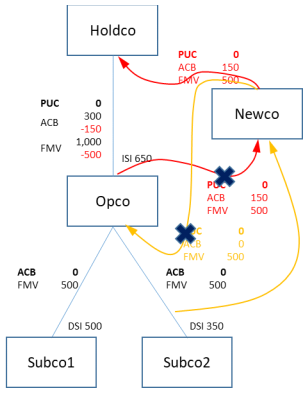

Instead of transferring to Newco shares of Opco having an ACB of $150, Holdco should transfer to Newco shares of Opco having a FMV of $500 and an ACB of at least $200 to avoid the misalignment of outside and inside ACB. A transfer of the full $300 of ACB of the shares of Opco held by Holdco to Newco is also acceptable since the ACB reflects the cost of indirect acquisition of the shares of Subco2.

Since the shares of Subco2 are transferred to Newco on a rollover basis, the DSI of $350 that Opco had in Subco2 is transferred over to Newco. Newco will have DSI of $350 on the shares of Subco2.

On a consolidated basis, the shares of Newco held by Holdco have an ISI of $150 since it represents the ISI of Opco that was transferred over to Newco.

Since ISI of Holdco in Opco is now fully transferred over to Newco, Holdco should no longer have ISI in the remaining shares owned in Opco. This is logical since the underlying value in Subco1 is unrealized and Subco1 has no DSI.

The formula for calculating ISI (below the Newco level) as reflected in slide #2 should still be valid and the calculation would be as follows:

ISI on the shares of Newco: ISI of Opco (that excludes the DSI of Opco) prior to reorg X ISI of entities transferred over to Newco / total ISI of all entities held by Opco prior to reorg

ISI on the shares of Opco after reorg: ISI of Opco prior to reorg X ISI of entities retained by Opco / total ISI of all entities held by Opco prior to reorg

Example 4

This is the same as Example 3, except that Subco1 has realized DSI of $500 after the acquisition of Opco by Holdco.

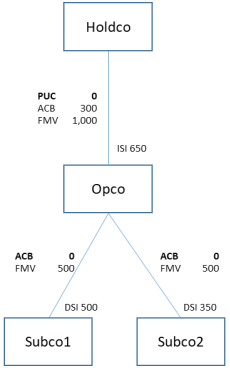

Opco would therefore have a total ISI of $650, being $500 in the shares of Subco1 and $150 in the shares of Subco2 (post-acquisition of Opco by Holdco). Note that the DSI of $200 of Subco2 pre-acquisition of control is reflected in the ACB of the Opco shares held by Holdco. The FMV of Subco1 was $500 and the FMV of Subco2 was also $500 prior to the reorganization.

If safe income were to be capitalized prior to the reorganization, Subco1 would pay a safe income dividend of $500 to Opco, Subco2 would pay a safe income dividend of $350 to Opco and Opco would pay a safe income dividend of $650 to Holdco. After capitalization of safe income, the situation would be as follows:

In this situation, Holdco has an ACB of $950 in the shares of Opco and, if Opco were to be wound-up, Holdco would directly own shares of Subco1 and Subco2 with an aggregate ACB of $850. Therefore, in this situation, the maximum ACB that Holdco could have in its subsidiaries does not exceed $950.

Reorganization possibility

Without going through the capitalization of safe income, Opco transferred Subco2 to Newco in a reorganization that qualified for the exemption under paragraph 55(3)(a). To effect the spin-off, Holdco transferred shares of Opco having an ACB of $150 and a FMV of $500 to Newco in consideration for shares of Newco. Opco then transferred shares of Subco2 having an ACB of nil and a FMV of $500 to Newco in consideration for shares of Newco. The shares held by Newco in Opco and by Opco in Newco are redeemed for a note and the notes are cross-cancelled.

Since the shares of Subco2 are transferred to Newco on a rollover basis, the DSI of $350 that Opco had in Subco2 is transferred over to Newco. Newco will have DSI of $350 on the shares of Subco2.

On a consolidated basis, the shares of Newco held by Holdco have an ISI of $150 since it represents the ISI of Opco that was transferred over to Newco.

Since $150 of ISI of Holdco in Opco is now transferred over to Newco, Holdco should have ISI of $500 in the remaining shares owned in Opco, which reflects the DSI of $500 of Subco1. The formula for calculating ISI (below the Newco level) would be as follows:

ISI on the shares of Newco: ISI to Holdco on the shares of Opco (that excludes the DSI of Opco) prior to reorg X ISI to Holdco of entities held by Opco that are transferred over to Newco / total ISI to Holdco of all entities held by Opco prior to reorg

ISI on the shares of Opco after reorg: ISI to Holdco on the shares of Opco prior to reorg X ISI to Holdco of entities held by Opco that are retained by Opco / total ISI to Holdco of all entities held by Opco prior to reorg

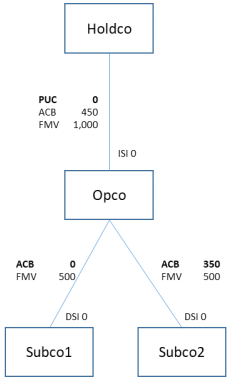

The situation after the reorganization would be as follows:

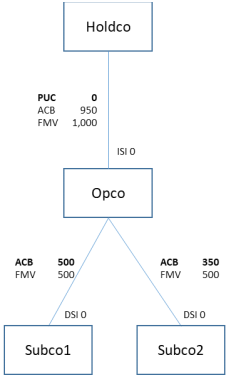

If safe income at all levels were to be capitalized after the reorganization, Holdco would have an ACB of $650 in the shares of Opco and an ACB of $300 in the shares of Newco. Opco would have an ACB of $500 in the shares of Subco1 and Newco would have an ACB of $350 in the shares of Subco2.

A subsequent disposition of the shares of Opco by Holdco after the dividend would result in a loss, but such loss is denied under subsection 112(3). On the other hand, if a safe income dividend of only $350 is subsequently paid on the shares of Opco held by Holdco, a disposition of the shares of Opco by Holdco would not result in a loss, but the portion of $150 of safe income has been lost.

This result is caused by the fact that only $150 of ACB of Opco has been transferred to Newco on the reorganization. If the ACB of Opco held by Holdco was streamed and transferred over to Newco for purposes of the reorganization, there would be no loss of ACB.

In this situation, it would be appropriate to stream the ACB of Opco and transfer the whole ACB of Opco to Newco in the course of the reorganization. The result would be as illustrated below:

Question 4: Sale of Taxable Canadian Property by a Partnership

Where “taxable Canadian property” (“TCP”) is sold by a partnership, the Canada Revenue Agency (“CRA”) has consistently administered the provisions of section 116 on the basis that it is the partners of the partnership which have disposed of the property. However we understand that it is the CRA’s policy to accept one notification of disposition filed pursuant to subsection 116(1) on behalf of all partners. See 2009-0317371I7 and 2012-0444081C6. Consistent with this position, we understand that if the CRA issues a section 116 certificate to the partnership pursuant to subsection 116(2), the certificate limit referred to in subsection 116(2) will not reflect the estimated proceeds of disposition of the TCP that are attributable to Canadian resident partners (because Canadian resident vendors are not subject to section 116 compliance requirements). A similar comment applies to a certificate issued pursuant to subsection 116(5.2).

Would the CRA confirm that a purchaser who purchases TCP or property described in subsection 116(5.2) from a partnership has no liability under subsections 116(5) or (5.3) in respect of the portion of the consideration paid to the partnership that, after reasonable inquiry, the purchaser believes is attributable to direct or indirect (through one or more other partnerships) partners of the partnership that are resident in Canada?

CRA Response

Subsection 116(5) may impose a liability on a purchaser who has acquired certain TCP from a non-resident person. Subsection 116(5.3) may impose a liability on a purchaser who has acquired from a non-resident person certain property described in subsection 116(5.2) (including certain property that may not otherwise be TCP for purposes of section 116). The amount of the purchaser’s liability under subsection 116(5) is computed by reference to the amount by which the cost to the purchaser of the acquired property exceeds the certificate limit set under subsection 116(2) (if any). The amount of the purchaser’s liability under subsection 116(5.3) is the excess of the amount payable for the property over the amount fixed in the certificate under subsection 116(5.2).

It is our view that the term “non-resident person” in section 116 refers to each partner individually, because subsection 96(1) does not deem a partnership to be a separate person for purposes of the withholding requirements in section 116. For the purposes of (inter alia) paragraph 2(3)(c) and section 116, each partner of the partnership is considered to have disposed of their respective interest in the property of the partnership for proceeds of disposition equal to the portion of the consideration that is proportionate to the partner’s interest in the property.

For the purpose of computing a purchaser’s liability, it is our view that the “cost to the purchaser of the property” or the “amount payable” by the purchaser for the property acquired from a non-resident person in paragraph 116(5)(c) or subparagraph 116(5.3)(a)(i) of the Act respectively excludes the portion of the consideration paid by the purchaser to a partnership that is reasonably attributable to the interest held by Canadian resident partners in the property through the partnership or through the partnership and other tiered partnerships.

Question 5: Article IV:6 of the Canada-US Treaty

Where the conditions in Article IV:6 of the Canada-U.S. Income Tax Convention (“Canada-US Treaty”) are satisfied, Canadian-source income, profit or gain that is earned by a resident of the U.S. through an entity (other than an entity resident in Canada) that is treated as fiscally transparent for U.S. tax purposes is deemed to be derived by that U.S. resident for the purpose of the Canada-US Treaty. In the Technical Explanation to the 2007 Protocol to the Canada-US Treaty, an example is given of a U.S. resident that owns a French entity that earns Canadian-source dividends and the entity is considered fiscally transparent under U.S. tax law. The Technical Explanation indicates that the U.S. resident is considered to derive the Canadian-source dividends for purposes of the Canada-U.S. Treaty and thus, the dividends are considered as being “paid to” the U.S. resident.

In a slightly more complicated example, a French corporation that is fiscally transparent for U.S. tax purposes, is wholly-owned by a partnership that is fiscally transparent for U.S. tax purposes. All the partners of the partnership are non-residents of Canada: some are residents of the U.S., some are residents of countries with which Canada has an income tax convention, and some are residents in countries with which Canada does not have an income tax convention. The French corporation, which is a resident of France for purposes of the Canada-France Income Tax Convention (“Canada-France Treaty”), receives dividends and interest payments from a Canadian corporation. The French corporation is not fiscally transparent under Canadian or French tax laws.

Can the CRA confirm that the Canadian payor of the dividends and interest can determine its withholding tax obligations in accordance with the relevant articles under either the Canada-France Treaty or the Canada-US Treaty, as appropriate? Specifically, a positive response would involve that where the conditions for Article IV:6 of the Canada-US Treaty are met, such that a portion of the dividends or interest is considered to be derived by U.S. residents eligible to benefits under the Canada-US Treaty, the Canadian payor can apply the relevant rate under either the Canada-France Treaty or the Canada-US Treaty. A positive response would also involve that to the extent that the Canada-US Treaty does not apply to the dividends or interest, the Canadian payor can determine its withholding tax obligations by applying the relevant rates under the Canada-France Treaty.

CRA Response

Where a person found for purposes of the application of the Canada-US Treaty (the “Treaty”) to be resident in the U.S. makes an investment into a Canadian corporation through a Limited Liability Corporation (“LLC”) that is fiscally disregarded in the U.S., without the application of Article IV:6 of the Treaty (“Article IV:6”), Canada’s longstanding position is that the benefits provided under Articles X and XI of the Treaty are not available on the dividends and interest paid by the Canadian corporation to the LLC. That conclusion is based on the fact that from a Canadian perspective, the U.S. LLC is not considered for purposes of the application of the Treaty to be a “resident” of the U.S.

The Canadian tax implications of the investment structure described above changed as a result of the addition of Article IV:6 by the 2007 Protocol to the Treaty (the “2007 Protocol”). Where the conditions of Article IV:6 are satisfied in respect of the investment structure described above, provided that the U.S. resident members of the LLC are “qualifying persons” under the Treaty in accordance with Articles XXIX-A(2) (“Qualifying Persons”), Canada is required to reduce the rate of tax under Part XIII of the Income Tax Act (“Part XIII”) imposed on dividends and interest paid to the LLC by the Canadian payor. However, the application of Article IV:6 does not alter Canada’s position that the LLC is not considered to be a resident of the U.S. for the purpose of the Treaty.

As mentioned in the question, where a French entity that is fiscally transparent under U.S. tax law but not under Canadian and French tax law is owned by a U.S. resident, the Technical Explanation to the 2007 Protocol provides that where all the conditions are met, Article IV:6 applies and the Canadian sourced income, profit or gain of the French entity is considered as being “paid to” the U.S. resident for the purposes of the Treaty. In such circumstances, from a Canadian perspective, the French entity remains the only taxpayer and the reduced withholding rate under the Treaty applies to the payments of dividends or interest.

The CRA is of the view that the French entity could alternatively claim the benefit of reduced withholding rates under the Canada-France Treaty. Assuming that the requisite conditions are met, the withholding tax rate under Part XIII would be limited by the lower rate of withholding on dividends or interest offered by either the Treaty or the Canada-France Treaty, if such lower rate is claimed. The result should be the same where there is a partnership between the French entity and the ultimate U.S. owner of the French entity. As previously mentioned by the CRA, the fact that there are multiple layers of fiscally transparent entities, on its own, should not preclude the application of Article IV:6.

In this case, there are multiple partners in the partnership which owns the French entity, and some of the partners are U.S. residents for the purpose of the Treaty while others are resident in other jurisdictions. It is our view that the benefit of reduced withholding rates under the Treaty can be claimed on a portion of a payment of dividends or interest that is deemed by Article IV:6 to be derived by U.S residents who are Qualifying Persons. In that context, where the reduced rate under the Treaty is applied to a portion of the payment, the other portion would be subject to the 25% tax rate imposed under Part XIII. Alternatively, the French entity could claim the reduced withholding benefit under the Canada-France Treaty with respect to the full amount of the payment of dividends or interest that it received from the Canadian payor. The CRA is of the view that the benefit of a reduced withholding rate under the Canada-France Treaty on the payment of dividends or interest received by the French entity cannot be claimed where such benefit is claimed under the Treaty. The Treaty and the Canada-France Treaty cannot both apply to a particular payment of dividends or interest that the French entity received from the Canadian payor.

The Canadian payor should determine its withholding obligation under Part XIII in accordance with the benefit that is applicable as described above. Before deciding to reduce the amount of Part XIII withholdings from a payment of this nature, any person responsible for deducting or withholding amounts on account of Part XIII tax is advised to obtain sufficient information to ascertain whether the particular amount will be considered to be derived by U.S. residents who are Qualifying Persons. The French entity could provide the Canadian payor with information that would support how the U.S. residents are considered to derive the income amount to be paid for the purposes of the Treaty. In this regard, the French entity could present the responsible person with the information asked for in Form NR301, Declaration of Benefits Under a Tax Treaty for a Non-Resident Taxpayer, Form NR302 Declaration of Benefits Under a Tax Treaty for a Partnership With Non-Resident Partners and/or Form NR303, Declaration of Benefits Under a Tax Treaty for a Hybrid Entity, as applicable in the particular circumstances, and certify the correctness of that information. It should be noted that obtaining Forms NR301, NR302 and NR303 does not exempt the payor from being liable for any deficiency in tax withheld.

Finally, where a person resident in Canada pays or credits an amount of interest or dividends to a non-resident, the person is required to issue a Form NR4 Statement of Amount Paid or Credited to Non-Residents of Canada to the non-resident payee on or before the last day of March following the calendar year in which the amount is paid or credited. This procedure applies even where a resident of the U.S. is considered to have derived the amount (or a portion of the amount) of interest or dividends paid or credited by virtue of Article IV:6 of the Treaty. For more information concerning the completion of NR4 information slips, please consult Guide T4061, NR4 – Non-Resident Tax Withholding, Remitting and Reporting.

Question 6: Multi-Lateral Instrument and “Principal Purpose” Test

The Multilateral Instrument (“MLI”) became effective January 1, 2020, for many of Canada’s income tax treaties. Among other provisions, the MLI contains an anti-avoidance rule (often referred to as the principle purpose test (“PPT”)). Unfortunately, there has been limited guidance on the specific situations in which the PPT may (or may not) apply. Moreover, it remains unclear the extent to which the PPT will be administered and applied in a manner similar to that of Canada’s domestic GAAR.

Can the CRA provide examples of:

- any fact patterns on which rulings have been requested or granted under the MLI; and

- any fact patterns on which the CRA has applied the PPT (and whether the CRA also applied GAAR in those situations)?

CRA Response

Canada has a longstanding, consistent and clear policy of preventing base erosion and international profit shifting. The CRA supports that policy inter alia through its administration of:

- s. 17, 18(4), 95, 212(3.1) to 212(3.94), 212.3 and 247;

- s. 245 to deny treaty benefits in cases of treaty abuse, as clarified through the retroactive amendment made in 2005 to the definition of “tax benefit” in s. 245(1) and to s. 245(4) and the enactment of s. 4.1 of the Income Tax Conventions Interpretation Act; and

- limitation on benefit and anti-avoidance provisions in different treaties.

The Government of Canada 2014 Budget entitled “The Road To Balance: creating Jobs and Opportunities” included a section “Addressing International Aggressive Tax Avoidance by Multinational Enterprises.” That section indicated that “Canada’s tax rules must constantly be reviewed to ensure that they maintain an appropriate balance between the objectives of competitiveness, simplicity, fairness, efficiency and protection of the tax base.” In that spirit, it made reference to the OECD’s base erosion and profit shifting project:

Other countries share Canada’s recognition of the importance of an effective international tax system. In February 2013, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) launched a project on base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS). The project aims to address international tax planning strategies used by multinational enterprises to inappropriately minimize their taxes, for example, by shifting taxable profits away from the jurisdictions where the economic activity has taken place. […] These multilateral efforts are consistent with the Government’s ongoing commitment to protect the Canadian revenue base and ensure tax fairness.

In keeping with that internationally shared objective of addressing base erosion resulting from the abuse of international tax treaties, Canada, along with over 100 other jurisdictions undertook the completion of the BEPS project, including the creation and implementation of the Multilateral Convention to Implement Tax Treaty Related Measures to Prevent Base Erosion and Profit Shifting ("MLI") in 2016. As of September 2020, 94 jurisdictions, including Canada, have signed the MLI which modifies numerous tax treaties to include a general anti-abuse rule in the form of the PPT and to update the preamble to those treaties to unequivocally state that they are for the purpose of eliminating double taxation without creating opportunities for non-taxation or reduced taxation through tax evasion or avoidance (including through treaty-shopping).

For the purposes of providing interpretive guidance on the application of the PPT, thirteen examples were included in the 2015 OECD’s Action 6 Final Report – Preventing the Granting of Treaty Benefits in Inappropriate Circumstances (pages 57 to 64): https://read.oecdilibrary.org/taxation/preventing-the-granting-of-treaty-benefits-in-inappropriate-circumstancesaction-6-2015-final-report_9789264241695-en#page18. These and other examples of the application of the PPT are now laid out in the Commentary to Article 29 of the OECD Model Tax Convention at paragraphs 182 and 187: https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/taxation/model-taxconvention-on-income-and-on-capital-condensed-version-2017_mtc_cond-2017-en#page601. In adopting the most recent version of the Model Tax Convention, no country registered an objection, reservation, or position against the PPT or the relevant interpretive guidance concerning its application in the Commentary. As a result, the CRA will look to this guidance for assistance in interpreting and applying the PPT.

Much of the concern expressed about uncertainty and the potential application of the PPT appears to center around questions as to the necessary indicia to support or rebut a reasonable conclusion that a transaction or arrangement had a principal purpose of obtaining a benefit under a tax convention, or what is required to establish that granting the benefits would nevertheless be in accordance with the relevant provisions of the convention in the particular circumstances.

As explained in paragraphs 178 to 181 of the OECD Commentary to Article 29, these questions are highly fact-dependent and linked to the particular taxpayers and their motives as well as the specific tax convention and the provisions and benefits thereunder in question.

In determining whether any arrangement or transaction has, as one of its principal purposes, the obtaining of a treaty benefit, the CRA would seek to ask a number of questions, including but not limited to:

- What are the direct and indirect results of the arrangement?

- What are the terms of the arrangement and do they lead to its results?

- What actions were undertaken to carry the arrangement into effect?

- What do the circumstances surrounding the arrangement, they way in which it was implemented, as well as its terms, indicate about the arrangement and its intended results?

- Could the non-tax objectives of the arrangement be achieved some other way? If so, is the arrangement more complex, more costly (not considering the tax benefit), or contain more steps than is necessary to achieve the non-tax objectives?

- Does the arrangement entail the use of hybrid entities, flow-through arrangements, or back-to-back transactions?

- Does the arrangement involve a change of residence or applicable tax convention?

- What are the non-tax benefit purposes for establishing each of the relevant entities or actions in each relevant jurisdiction?

- Is the existence of any entity or action in the arrangement explainable only if it is principally concerned with the obtaining the relevant benefit?

- Absent any tax benefit, are there quantifiable financial benefits arising from the arrangement?

- Is there a discrepancy between the substance of what the arrangement achieves and its legal form?

- Does the arrangement result in a change in nature of payments?

- Does the arrangement result in the avoidance of a specific taxing rule? For example, does it avoid the existence of a permanent establishment or to avoid a test which would otherwise limit access to a benefit?

The above questions may also be relevant in respect of the GAAR for taxation years currently audited.

The Income Tax Ruling Directorate has not yet been asked to provide an advance income tax ruling on the application of the PPT as introduced by the MLI, and the CRA has not yet audited taxation years in which the changes to tax treaties introduced by the MLI are in force and effect.

The CRA has confirmed at the 2019 CTF Conference round table the creation of its Treaty Abuse Prevention Committee. The TAP Committee will provide recommendations to the CRA on the administration of the GAAR in a tax treaty context and of the general anti-avoidance rule introduced by the MLI. We note that the Supreme Court of Canada recently granted leave to the Crown in The Queen v. Alta Energy Luxembourg S.A.R.L.,[2020 FCA 43] involving the potential application of the GAAR to a benefit claimed by the taxpayer under the Canada-Luxembourg Tax Convention.

As with the GAAR, in deciding on any application of the PPT to a particular case, the CRA will diligently and fairly fulfill its role to administer the provisions of the Income Tax Act as informed by the application of tax treaties in light of their object, spirit and purpose in keeping with the interpretation guidelines provided by the Courts.

Question 7: Use of a Cottage by the Children of the Settlor of an Alter Ego Trust or a Joint Spousal or Common-Law Partner Trust

At the 1988 and 1989 Round Tables, the CRA commented on whether a benefit would arise under section 105 from the use of property, such as a cottage, held in trust for an individual in circumstances where no rent is paid but the costs of maintenance and upkeep are paid. The CRA took the position that the use of a cottage property by a beneficiary does constitute a benefit. However, with respect to property owned by a trust that had been or would have been personal-use property (“PUP”) of an individual, the CRA would generally not seek to assess a benefit where the trust is effectively standing in the place of the individual and no benefit or tax advantage would have arisen if the individual, instead of the trust, had allowed the use of the property. PUP is as defined in section 54 and includes homes, cottages, boats, and cars. The CRA confirmed its position in CRA Documents 9707305 and 2012-0470951E5.

Can the CRA confirm that its position will also apply to a trust that is an alter ego trust or a joint spousal or common-law partner trust?

CRA Response

Consistent with our previously published comments, although it is the CRA’s position that the use of trust property by a beneficiary of the trust constitutes a benefit for the purposes of subsection 105(1), in the case of PUP owned by a trust, the CRA will generally not assess a benefit for the use of that property. In this regard, PUP of a trust will, in accordance with the definition in section 54, include property (such as homes, cottages, boats, cars, etc.) owned primarily for the personal use or enjoyment of a beneficiary of the trust or any person related to the beneficiary.

Consequently, where, pursuant to the terms of the trust indenture or will, a trust owns PUP for the benefit, enjoyment or personal use of a beneficiary, our position is that a taxable benefit under subsection 105(1) will generally not be assessed to that beneficiary for the rent-free use of the property. Notwithstanding the above comments, a benefit in respect of the upkeep, maintenance, or taxes for such property may arise pursuant to subsection 105(2).

Pursuant to subsection 73(1), an individual (other than a trust) can transfer capital property on a tax-deferred basis, where certain conditions are met. In order for subsection 73(1) to apply, the following conditions must be met:

- at the time of the transfer of property, both the transferor of the property and the transferee must be resident in Canada;

- the transferor must not elect out of the rollover rule; and

- subsection 73(1.01) must apply in respect of the transfer (a “qualifying transfer”).

Subsection 73(1.01) provides that, subject to the requirements of subsection 73(1.02), qualifying transfers include, inter alia, transfers to a trust created by the individual transferring the property:

- that meets the requirements of subparagraph 73(1.01)(c)(ii), such that the individual is entitled to receive all the income of the trust arising before his or her death and under which no person except that individual may receive or otherwise obtain the use of any of the income or capital of the trust before that individual’s death; or

- that meets the requirements of subparagraph 73(1.01)(c)(iii), such that the individual and his or her spouse or common-law partner is entitled to receive all the income of the trust arising before their deaths and under which no one other than the individual or the individual’s spouse or common-law partner is permitted to receive or otherwise obtain the use of any of the income or capital of the trust before the death of both the individual and the individual’s spouse or common-law partner.

Subsection 73(1.02) imposes additional conditions that must be met in order for a trust to meet the requirements of either subparagraph 73(1.01)(c)(ii) or (iii). Generally, in either case:

- the trust must be created after 1999; and

- the individual must be at least 65 years of age at the time the trust is created, or, the transfer of property by the individual must involve no change in beneficial ownership of the property and no person (other than the individual) or partnership has any absolute or contingent right as a beneficiary under the trust (determined with reference to subsection 104(1.1)).

A trust described in subparagraph 73(1.01)(c)(ii) that meets all of the relevant conditions outlined above will generally be an “alter ego trust” as defined in subsection 248(1). Similarly, a trust described in subparagraph 73(1.01)(c)(iii) that meets all of the relevant conditions outlined above will generally be a “joint spousal or common-law partner trust” as defined in subsection 248(1).

As such, where pursuant to the terms of the trust indenture an alter ego trust or a joint spousal or common-law partner trust owns PUP for the benefit, enjoyment or personal use of a beneficiary during their lifetime, our position is that a taxable benefit will generally not be assessed to that beneficiary for the rent-free use of the property by that beneficiary.

However, when considering the use of the PUP by another individual, one must remember that for an alter ego trust, in order to meet the conditions outlined in paragraph 73(1.01)(c), the alter ego trust must be a trust under which no person except the settlor may receive or otherwise obtain the use of any of the income or capital of the trust before the settlor’s death. Similarly, in the case of a joint spousal or common-law partner trust, the terms of the trust must provide that no person other than the settlor and their spouse may obtain the use of any of the income or capital of the trust before the later death of the settlor and their spouse.

Question 8: Salary Deferral Arrangements (SDAs) and Formula-Based Appreciation Plans

It is not uncommon for a private corporation to have an equity-based incentive plan under which participating employees are granted units, the value of which is determined using formulas (“formula-based appreciation plans”). These formulas often involve various future oriented financial metrics of the corporation such as earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (“EBITDA”). Units granted under such plans generally do not have any intrinsic value at the date of grant, but may increase in value over the duration of the plan, depending on the measured results.

The CRA has previously provided favourable rulings that certain formula-based appreciation plans were not salary deferral arrangements (“SDAs”) as defined in subsection 248(1). However, we understand that the CRA will no longer consider such ruling requests.

Can the CRA comment on why it has changed its practice?

CRA Response

While examining a recent ruling request on whether a proposed formula-based appreciation plan is a SDA, we encountered issues that caused us to revisit our willingness to consider such rulings requests.

One of these issues relates to the fact that the determination of whether any given incentive plan is a SDA must be made on an annual basis from the date of grant, and from the perspective of each employee participating in the plan in the context of the specific awards granted to that employee, taking into account all known facts and circumstances up to that point. It has become clear to us that it is simply not possible to be reasonably certain, at the time of a ruling request, that a formula-based appreciation plan would never become a SDA at some point in the future due to changes in the relevant facts and circumstances specific to the employee, the employer or the business environment in which it operates.

Another issue is that such plans are vulnerable to manipulation. As we cannot reasonably account for such risk in the context of a ruling request, we believe that such a determination would be more appropriately addressed at a later stage of the compliance continuum.

As a result, the CRA will no longer consider any ruling requests relating to the determination of whether any given formula-based appreciation plan is a SDA, unless the plan is a share appreciation rights plan as described in ATR-45, or the ruling request pertains to whether one of the enumerated exceptions listed in the SDA definition applies.

This change in administrative policy does not mean that the CRA considers all formula-based appreciation plans to be SDAs. On the contrary, we accept that it is quite possible that many such plans will not be a SDA where the underlying formula closely approximates the fair market value of the relevant shares of the corporate employer over the duration of the plan. However, the CRA will no longer make such a determination in the context of a ruling request.

See technical interpretation 2020-0850281I7 for more details.

Question 9: Entity classification of UK LLP

Under the United Kingdom’s Limited Liability Partnerships Act 2000 (as amended), a limited liability partnership governed by that statute (“UK LLP”) is treated in the United Kingdom as a separate legal entity, but the profits of its business are taxed as if the business were carried on by partners in partnership, rather than by a body corporate.

Does the CRA view a UK LLP as a corporation or as a partnership for Canadian tax purposes?

CRA Response

When determining the form of association under Canadian commercial law of a foreign business association for Canadian tax purposes, the CRA generally applies the following two-step approach:

- determine the characteristics of the foreign business association under foreign commercial law; and

- compare these characteristics with the characteristics of recognized categories of business associations under Canadian commercial law in order to classify the foreign form of business association under one of those categories.

The following characteristics are common to corporations incorporated under Canadian federal or provincial legislation:

- legal personality and existence, separate and distinct from its members;

- ability to carry on its activities in its own name;

- ability to acquire and own rights and property (including the property used in carrying on its business) and to incur liabilities in its own name (which must not be the rights or liabilities of the members);

- capacity of taking legal proceedings in its own name and exposure to being sued; and

- the issuance of some form of “share capital” or equity interest.

Generally, to qualify as a partnership under Canadian provincial law, there are three essential elements:

- a business;

- carried on in common by two or more people;

- with a view to profit.

The CRA is of the view that the general characteristics of a UK LLP more closely resemble the general characteristics of a corporation than the general characteristics of other forms of business association under Canadian commercial law for the following reasons:

- A UK LLP has a legal existence separate from its members.

- A UK LLP, and not its members, carry on the business.

- A UK LLP, and not its members, acquires and owns property in its own name for use in its business, and is responsible for any debts or obligations incurred as a result of carrying on its business.

- The capital of a UK LLP serves the same function as the share capital of a corporation.

It should be noted that the classification of a particular UK LLP remains to be determined on a case-by-case basis. Taxpayers may wish to request an advance income tax ruling if they are contemplating transactions involving a foreign entity whose legal form for Canadian income tax purposes is uncertain.

Question 10: Refreezes and corporate attribution rules in subsection 74.4(2)

Refreeze transactions generally involve an individual exchanging preferred shares received on an earlier estate freeze for newly issued preferred shares with a redemption amount equal to the current (lower) equity value of the underlying corporation. The preferred share redemption amount is thus “reset” at present values.

Subsection 74.4(2) provides for an attribution of income when an individual transfers or loans property to a corporation and certain conditions are met. One condition is that the loan or transfer be for the purpose of reducing the individual’s income and to benefit a “designated person” (defined in subsection 74.5(5)) in respect of the individual. If the rule is applicable, the individual may be subject to an annual deemed interest benefit.

If subsection 74.4(2) applies to the original estate freeze, the preferred shares received on the refreeze do not appear to reduce the “outstanding amount” (as determined under subsection 74.4(3)) on which the deemed interest benefit is computed under subsection 74.4(2). In addition, if the refrozen preferred shares are redeemed, the “outstanding amount” seems to only be reduced to the extent of the value of those shares, leaving a potential indefinite “outstanding amount” on which the corporate attribution rules could continue to compute deemed interest income.

Does the CRA agree that:

A. shares received on a refreeze do not reduce the “outstanding amount” (as determined under subsection 74.4(3); and

B. the redemption of refrozen preferred shares for cash consideration reduces the “outstanding amount” only to the extent of the value of those shares leaving an indefinite “outstanding amount” on which the corporate attribution rules will continue to compute deemed interest income?

CRA Response (A)

Generally, it is expected that a taxpayer will not undertake an estate freeze that is subject to the attribution rule in subsection 74.4(2). However, if an estate freeze is subject to subsection 74.4(2), as noted above, the deemed interest benefit is computed based on the “outstanding amount” determined under subsection 74.4(3). Paragraph 74.4(3)(b) applies where money or property is loaned and, therefore, would not generally apply to the transfer of shares under an estate freeze. Paragraph 74.4(3)(a) provides as follows:

(a) in the case of a transfer of property to a corporation, the amount, if any, by which the fair market value of the property at the time of the transfer exceeds the total of

(i) the fair market value, at the time of the transfer, of the consideration (other than consideration that is excluded consideration at the particular time) received by the transferor for the property, and

(ii) the fair market value, at the time of receipt, of any consideration (other than consideration that is excluded consideration at the particular time) received by the transferor at or before the particular time from the corporation or from a person with whom the transferor deals at arm’s length, in exchange for excluded consideration previously received by the transferor as consideration for the property or for excluded consideration substituted for such consideration;

Subparagraph 74.4(3)(a)(i) takes into account consideration received on the initial transfer and, therefore, would not apply to an exchange of shares under a subsequent refreeze. Subparagraph 74.4(3)(a)(ii) would also not apply as the shares received on the refreeze constitute “excluded consideration”, as that term is defined in subsection 74.4(1). Therefore, we agree the shares received on a refreeze do not reduce the “outstanding amount” under subsection 74.4(3).

CRA Response (B)

Subparagraph 74.4(3)(a)(ii) will reduce the outstanding amount by the fair market value, at the time of receipt, of consideration from the corporation in exchange for excluded consideration previously received by the transferor as consideration for the property or for excluded consideration substituted for such consideration. Therefore, we agree the redemption of refrozen preferred shares for cash consideration will reduce the “outstanding amount”, but only to the extent of the fair market value of those shares. While the redemption of the refrozen preferred shares will leave an “outstanding amount” on which the corporate attribution rules will continue to compute deemed interest income, the corporate attribution rules will only apply during the period the conditions in paragraphs 74.4(2)(a), (b) and (c) continue to be met.

Question 11: Refinancing Prescribed Rate Loans and the Attribution Rules

An individual (other than a trust) has a prescribed rate loan at 2% for $100,000 (“Loan 1”). The borrowed money was used to purchase securities for $100,000. The securities now have a value of $200,000. The individual wants to refinance the loan at 1%. The individual wishes to sell half the securities and use the proceeds to repay the loan. The individual would then borrow $100,000 at the prescribed rate of 1% (“Loan 2”). The proceeds of Loan 2 will be used to purchase new securities for $100,000.

Can the CRA confirm that the attribution rules will not apply to the securities that are still owned and were purchased with Loan 1? Can the CRA confirm that the attribution rules will not apply to the investments purchased with Loan 2?

CRA Response

In respect of the repayment of Loan 1, as stated in paragraph 22 of IT-511R - Interspousal and Certain Other Transfers and Loans of Property, “If property has been acquired with a loan that satisfied the requirements of subsection 74.5(2) and the loan is repaid, neither subsection 74.1(1) nor 74.2(1) will apply after the repayment to income earned on the property or capital gains arising on the disposition of the property.”

In respect of Loan 2, the proceeds of that prescribed rate loan are used to purchase new investments. Subsection 74.5(2), which provides an exemption from the attribution rules contained in subsection 74.1(1) and section 74.2, could apply with respect to Loan 2 if all the conditions stated therein are satisfied.

Moreover, subsection 74.1(3), which inter alia ensures that the attribution rules will continue to apply where a new loan is used to repay an existing loan that was used to acquire property, would not technically apply in this situation as the proceeds from Loan 2 are not used to repay Loan 1.

Question 12: Impact of COVID-19 on previous APAs and current MAPs

The economic impact created by the international response to the COVID-19 pandemic has and will negatively impact the growth prospects and profitability in many industry sectors in 2020, 2021, and potentially beyond.

A. What are the CRA’s views on how this particular impact will affect:

(i) the Mutual Agreement Procedures (“MAP”) cases that are currently being negotiated and the previously negotiated Advance Pricing Arrangements (“APA”); and

(ii) the benchmarking analyses that are used to establish transfer pricing policies and prepare transfer pricing compliance documentation?

B. Is the CRA considering amendments to historic transfer pricing policies to reflect impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on business economics, risk sharing, etc.?

CRA Response (A)(i)

MAP cases that are currently being negotiated

To the extent that the MAP cases currently being negotiated cover taxation years that precede the 2020 COVID-19 crisis, the CRA does not envision any impacts on these cases or the need to adopt special considerations on account of the COVID-19 crisis. As a matter of practice, the approach used by the CRA to resolve double taxation on filed taxation years is to focus on the period(s) in question. The CRA does not take into account future years (or specifically, events that have transpired in later periods) when negotiating MAPs.

Previously negotiated APAs

APAs are undertaken on the basis that the past is a reasonable projection of the future. When entering into an APA, it is assumed that the covered transactions and corresponding facts and circumstances (such as the functions, assets and risks of the transacting parties and the business and economic circumstances) will not materially differ from past years. However, as a matter of practice, all APAs entered into by the CRA include a series of critical assumptions – that, if breached, may require that the terms of the APA be re-visited. Establishing whether a critical assumption has been violated is a question of fact that will depend on the specific terms and conditions of the APA and the changes to the underlying business and economic circumstances experienced by the taxpayer(s).

COVID-19 and the economic uncertainty created by the crisis also present a significant challenge as it pertains to APAs that are currently in the process of being negotiated. At this time, the CRA does not have a formal policy or approach to guide how APAs are to be negotiated to take into account these circumstances, nor does it believe (at this time) that an across-the-board policy is an appropriate measure given that not all industries (or taxpayers) will be impacted in the same manner or degree. That is not to say that certain allowances (for example – the use of limits / critical assumptions to collar or point to a specific return within a range) will not be required for certain taxation years over a proposed APA term; however, when and how this is implemented will be addressed on a case-by-case basis.

CRA Response (A)(ii)

Benchmarking analyses that are used to establish transfer pricing policies and prepare transfer pricing compliance documentation

The benchmarking results will be impacted by the greater macroeconomic conditions the market faces.

In transfer pricing, the CRA typically looks at year-specific comparable company data in determining arm’s-length profitability. This will not change for the COVID-19 pandemic years. The CRA’s review of benchmarking studies will be unaffected as well. The benchmarking studies will continue to be based on the information gathered in the audit and due diligence process.

The process will be unchanged and remain rooted in the underlying analysis of the functions, assets and risks faced by the tested party which will inform the benchmarking criteria.

CRA Response (B)

The CRA is not considering across-the-board changes on its historic transfer pricing policies. However, the COVID-19 crisis may impact the future selection and use of transfer pricing methodologies on a case-by-case basis.

Question 13: Reimbursement of Equipment

At the April 14, 2020, APFF webinar on tax aspects of COVID-19 measures, the CRA was asked two questions: (1) Is an allowance paid by the employer to an employee for the purpose of acquiring equipment for teleworking a taxable benefit for the employee? (2) Would the CRA’s response be different if the amount paid by the employer is conditional on a proof of purchase being submitted by the employee?

For ease of reference, the April 14, 2020 position can be found in 2020-0845431C6, “Taxable Benefit Working From Home”. In that technical interpretation, the CRA indicated that the allowance is taxable for the employee in the first scenario. In the second scenario, it is a question of fact. In the context of the COVID-19 crisis, the CRA said that it is willing to accept that the reimbursement of an amount not exceeding $500 for the purchase of personal computer equipment will not be taxable if it is mainly for the benefit of the employer.

Would the CRA please indicate whether the $500 reimbursement amount will be increased, and whether increased or not, if its position on the amount reimbursed for the “purchase of personal computer equipment” will be expanded to include the purchase of home office furniture, such as desks, chairs, etc.

CRA Response

In technical interpretation F2020-0845431C6, the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) outlined its administrative position concerning the tax treatment of employer reimbursements of up to $500 for computer equipment purchased by employees, to enable them to perform their employment duties at home during the COVID-19 pandemic. Employees must submit receipts to support their purchases.

This administrative position will similarly apply to employer reimbursements for home office equipment (for example, a desk, office chair, etc.) purchased by employees.

It should be noted, however, that the $500 reimbursement amount is in respect of each employee rather than each piece of computer or office equipment that an employee may purchase. For example, if an employee purchases a computer for $400 and an office chair for $250, an employer can reimburse the employee up to $500 without the employee receiving a taxable benefit under the administrative position. By contrast, if the employer reimburses the employee the full amount for these purchases, the amount over $500 (that is, $150) must be included in the employee’s income.

While there are no current plans to increase the $500 reimbursement amount, the CRA will continue to carefully monitor all developments relating to the COVID-19 pandemic and will take further action as necessary.

Question 14: Section 86 Reorganization of Capital

Section 86 allows for a tax-free exchange of shares where there is a reorganization of capital.

The CRA states that articles of amendment need to be filed in order to meet this condition. Views Doc. No. 2010-0373271C6 [October 8, 2010]: The CRA stated that “in the context of subsection 86(1) …, a reorganization of the capital of a corporation should normally require amendments to the articles of incorporation.”

Views Doc. No. 2000-0048075 [February 22, 2001]: This document provides an example of the application of Section 86 in the context of a foreign affiliate. The CRA confirms that when the articles of association or other constating documents of a foreign affiliate are amended to authorize a new class of common shares a reorganization of capital is undertaken. In addition, the surrender of shares for fair market value is also required.

Views Doc. No. 9233955 [January 13, 1993]: The CRA takes the position that “where a corporation’s existing capital structure provides for it, the issuance of additional shares by the corporation would not of itself be such a reorganization whether the additional shares are issued pursuant to a rights offering or otherwise.”

Views Doc. No. RCT 5-3240 [May 20, 1987]: The CRA expresses the opinion that “the operation of an existing set of rights, conditions, or obligations [(such as where a share carries an automatic conversion right)] cannot be said to be a reorganization for purposes of section 86.”

The problem is that reorganization of capital is not defined in the Act nor is it a concept widely used in corporate law.

It is not uncommon for companies to include multiple share classes in their corporate structure in contemplation of subsequent reorganizations or restructurings. That being said, to ensure that the rollover treatment is available under subsection 86(1), articles of amendment are often still filed.

The question is whether this is necessary where the corporation had the foresight to provide for a wide range of classes of shares.

Arguably the CRA’s view is too narrow and an exchange of shares by a shareholder for new shares with different rights and restrictions is also a reorganization of capital.

Will the CRA reconsider its previous position and confirm that articles of amendment need not be filed to meet the condition in subsection 86(1) that there has been a reorganization of capital?

CRA Response

The CRA’s position on the application of subsection 86(1) has not changed, i.e., a reorganization of capital in the context of subsection 86(1) should normally require amendments to the articles of incorporation. As noted in the response in document 2010-0373271C6, even if subsection 86(1) does not apply in a given situation, another rollover provision such as section 51 or 85 of the Act may apply, depending on the circumstances.

1 We gratefully acknowledge the following CRA personnel who were instrumental in helping us prepare for this Round Table: Angelina Argento, Tom Baltkois, Nicolas Bilodeau, Stéphane Charette, Michael Cooke, Ina Eroff, Kanwal Graham, Kah Foo Koh, John Meek, David Palamar, Marina Panourgias, Katie Robinson, Marie-Claude Routhier, Louise Roy, Sandra Snell, Marc Ton-That, Allison Thomas, Nerill Thomas-Wilkinson, Grace Tu, Tobias Witteveen and Dave Wurtele.

2 Michael A. Hiltz, "Section 55: An Update," in Selected Income Tax Aspects of the Purchase and Sale of a Business, 1984 Corporate Management Tax Conference (Toronto: Canadian Tax Foundation, 1984), 40-46.

3 Lamont Management Ltd. v. the Queen 2000 D.T.C. 6256 (FCA).

4 Brelco Drilling Ltd. v. The Queen 99 D.T.C. 5253 (FCA).

5 In The Queen v. Nassau Walnut Investments Inc. 97 D.T.C. 5051 (FCA), the court agreed with the following submission by the crown: “assuming that the other requirements of that provision are satisfied, so long as the approach taken by the Minister in allocating safe income is reasonable, subsection 55(2) should apply regardless of whether the method chosen by Nassau could also be considered reasonable.”

6 The Queen v. Kruco Inc. 2003 D.T.C. 5506 (FCA), at paragraph 45. Note that the Kruco decision was on the application of subsection 55(2) prior to the 2015 amendments.